Banana Logic: Butterflies instead of Poison (ESP)

On the Canary Island of La Palma in Spain, we discover that the logical way to grow bananas is with butterflies instead of poison. Fran GarLaz explains why and how.

Contributes to achieving the following UN Sustainable Development Goals:

When the northeast trade winds meet the Canary Islands’ mountains, they are considerably disturbed. Between the islands and around their capes the winds strengthen considerably, creating acceleration zones. On the leeward side, it is calmer, with wind shadows of up to a dozen kilometres long. For our trip from Tenerife to La Palma we choose the windy route along the north sides of the island. It will mean more wind, but at least we’ll be able to sail. Yet it’s tough sailing, especially when we tack our way around Tenerife. Luci lists considerably, dives into one wave after another and gets a lot of water on deck. After a day and a night of sailing, we are happy to drop the anchor behind the protective breakwater of Tazacorte.

Banana Desert

From our anchorage we see why La Palma is known for its bananas. Directly behind the beach with black, volcanic sand is a steep cliff. Above it large, green leaves indicate the presence of banana plants. We kayak to the beach and climb a makeshift staircase built against the rocks. Once at the top, thousands of banana plants surround us. It is completely silent. There are no other plants, no buzzing insects and singing birds, just a man in a white protective uniform who sprays something on the plants. “Why would you need a protective uniform to work in the field, when these bananas are considered safe to eat?” Ivar wonders.

Banana Museum

Next to the plantations a colourful building houses a banana museum. Inside it we learn that the British introduced the banana plants to La Palma at the end of the 19th century. It became a success. The bananas thrive on the fertile volcanic soil and in the sunny climate. Banana plantations quickly spread all over the island, mostly as monoculture plantations. Yet in such circumstances insects and fungi can spread easily and harm the banana plants, leading to reduced harvests. It explains why since the 1960s toxins have been used to destroy them.

That battle continues to this day. Insects and fungi can become resistant over time, so there is a constant need for new types of agricultural poisons. However, those toxins kill almost all life in the soil, pollute the drinking water and leave residue behind in the bananas themselves. Despite these drawbacks, this way of working still characterizes the banana plantations on the island today. We wonder: how logical is that?

Banana Jungle

Fran GarLaz takes a different approach. He is the founder of the banana plantation named PlátanoLógico. As soon as we walk through the gate of his plantation, we see the difference. We’ve stepped into a real jungle. Next to the banana plants, we spot flowers, broccoli, papaya and mangos. Butterflies and birds fly all around us, while Fran enthusiastically delivers his story.

“Did you know that the banana plant is not a tree?” Fran begins. “It is actually the world’s largest herb!” He looks full of energy, and uses his knife regularly to prune, to demonstrate the anatomy of a banana plant, or to show richness of the soil. “Although my focus is on growing bananas, I take into account that in nature everything is connected to each other. The broccoli and flowers, for example, attract butterflies and insects. These attract the birds, which feed on them. And they also eat insects that are harmful to the bananas.” Further down we find ourselves between sheep, ducks and donkeys. “Together with the biomass from pruning, the animal manure helps to fertilize the soil. And the stray ducks keep the snail population in check. One can never have too many snails, although it is possible to have too few ducks”, Fran quips. We notice it is a real food forest, for all life forms here. “It took nature billions of years to form really productive ecosystems, and they are radically organic. All I try to do is maintain a balanced ecosystem and work with nature instead of against it”, Fran summarizes his philosophy.

Banana Rebellion

The plantation didn’t’ start out as lush as it is now. “When I bought this site nine years ago, it was a conventional banana plantation. Immediately I started planting indigenous flowers, plants and trees among the banana plants. I also added different types of banana. And I have never used agricultural poisons. This allowed the ecosystem to recover itself. Biodiversity has increased enormously since then,” Fran laughs.

“When the neighbours received word of my rebellious cultivation method without poisons, they were afraid that harmful insects and fungi would infect their bananas. I told them their production methods are not sustainable. They spray with poisons six to eight times a year to kill pests. They need synthetic fertilizers to feed their dead soil. Without continuous inputs from the chemical companies, their production would end very quickly. Over time I managed to convince them that I had no problems with pests. The diversity within the ecosystem ensures that there are enough natural enemies. Moreover, the resistance of the plants and trees against pests and diseases has increased.” According to Fran, the neighbours are happy now. “Their banana plants that are right next to mine, are doing better than ever!”

Banana Connections

We understand that a healthy ecosystem produces poison-free food, but how is it possible that increasing biodiversity reduces plant diseases so much, we wonder? Fran explains: “The diversity in plants creates less concentrated food sources for specific pests. In addition, the banana plants are connected to other plants via their roots systems. This way they chemically exchange information about pests. This allows them to prepare against attacks, for example by producing a substance that repels the pest or attracts their natural enemies. In order to do that, the plants use a variety of chemicals and odours. More and more scientific studies indicate that plant chemistry is much more complex than previously thought, and is an important natural defence mechanism that maintains health in a balanced ecosystem.” Aha, now I also understand why monocultures don’t exist in nature”, Ivar says.

Banana Economics

We ask Fran about the yields at PlatanoLógico. “The banana harvest per m2 is around 80% of a typical monoculture plantation. Considering that the plants are planted further apart, that’s an excellent yield,” Fran explains. “In addition to bananas I can also harvest papayas, mangos, broccoli and even coffee!” he adds, smiling.

According to Fran, it is also financially profitable. “My bananas are certified organic and can therefore be sold at a premium. I also save costs for not having to buy agricultural poisons and synthetic fertilizer.” We wonder if it is more work. “Yes, it is more work to maintain so many species of plants and animals, but I have hundreds of thousands of volunteers who help me!” We look at him somewhat bewildered. “All insects, birds, and worms work with me!” Fran laughs.

Banana Philosophy

“Let me share a bit of philosophy with you,” Fran continues. “I believe we are living at the most important moment in the history of humanity. Global ecosystems are in a death spiral, mainly because of our industrial way of food production. Our actions in the next ten to twenty years are crucial for the survival of our species on this planet. Our only sustainable choice is to work with nature and become radically organic.”

At PlátanoLógico Fran proves that radical changes are not only possible, but actually lead to better results. His approach casts doubt on the predominant logic of banana cultivation on La Palma. By cleverly combining different trees and plants, Fran stimulates biodiversity on his plantation. He succeeds in achieving a healthy harvest without using agricultural poisons and synthetic fertilization because the ecosystem on his plantation is in balance. His collaboration with nature is literally bearing fruit.

Banana Health

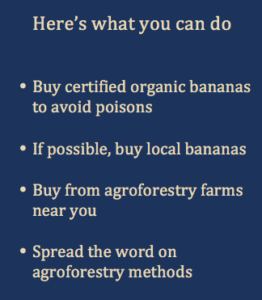

Fran’s system is not only better for biodiversity, but also the health of the soil, the groundwater and the bananas. Also, his plantation workers do not need protective clothing to protect their health. Finally, Fran’s agroforestry method also provides a healthy income. If it can be done with bananas, why not with other food crops?

We are inspired by Fran’s success and feel privileged to have learned so much from him. As a farewell present, Fran gives us a bunch of bananas. Never before have we tasted bananas with so much flavour. “I only want bananas from food forests”, Floris exclaims enthusiastically after the first bite. “They taste much better!” “And are toxic free”, Ivar winks. Quite logical, isn’t it?

Related Sustainable Solutions

Smart with Seaweed (NZL)

In New Zealand we learn how seaweed can be used to improve soil biology, with significant environmental and economic benefits for all farm types.

Urban Gardening (NZL)

In New Zealand’s cities we discover various ways of urban gardening and learn about the many benefits of growing food in cities.

Improving Children's Health with Veggies (PER)

High in the Peruvian Andes, poor school children learn how to grow and cook healthy, organic veggies. An example for the world?

Meatless in Buenos Aires (ARG)

In the beef capital of the world, the tide is turning in favour of plant-based diets. Good news for human health, animals, nature, and the climate.

Alda's Organic Neighbourhood Farm (URY)

Organic farmer Alda explains how fertile soil enables her to grow food without poison, increases biodiversity, and has positive climate effects.

Natural Coffee (BRA)

We visit a coffee forest in Brazil and learn all about the environmental and social benefits of agro-ecology.

Food Forests (BRA)

In Brazil, Ernst Götsch explains to us how to grow healthy food in cooperation with the forest.

Bananalogic (ESP)

On the Canary Island of La Palma in Spain, we discover that the logical way to grow bananas is with butterflies instead of poison.

Olive Oil (GRC)

In Greece we take a closer look at olive oil, which is an integral part of Greek history and culture. We discover ways of growing olives sustainably.

Slow Food (ITA)

The Slow Food movement promotes food that is good for the consumer, good for the producer, and good for the planet.