Social Sustainability at Mondragon (ESP)

At Mondragon, employees are owners, salaries and profits are fairly distributed, there is solidarity among cooperatives, and education is held in high esteem.

Contributes to achieving the following UN Sustainable Development Goals:

The Spanish Basque Country is home to the Mondragon Group. This multinational enterprise is made up of diverse cooperatives, among them industrial companies, banks and one of Spain’s largest supermarket chains. Each cooperative is owned by its employees and income differences among employees are small. Perhaps not coincidentally, unemployment in the region is low. This is striking, because desempleo is a major social issue in Spain. In addition, like in many other countries, wealth in Spain has spread more and more unevenly in recent decades, as highlighted by French economist Piketti in Capital in the 21st century. Recognising wealth inequality as a systemic problem and a threat to social stability, we wonder if Mondragon makes a good example of social sustainability? Curious to learn more, we cross the Bay of Biscay and moor in Bilbao.

A Large Group in A Small Basque Mountain Town

On our way to the bus station in Bilbao we pass a few branches of Mondragon cooperatives: Laboral (a bank), Eroski (a supermarket) and Eroski Viajes (a travel agency). The Mondragon Group also has industrial cooperatives, which produce machines and auto parts and deliver business-to-business, as well as schools, a university and a research & development laboratory.

With an annual turnover of around €12 billion, Mondragon is in size the seventh company in Spain. Its headquarters are in the Basque mountain village with the same name, except for the accent: Mondragón, our destination.

Brainchild of A Priest

At the group’s headquarters, we meet communications director Ander Etxeberria. He explains to us how the cooperatives started. “Mondragon is the brainchild of José María Arizmendiarrieta. He was a priest, so for him human dignity and solidarity were self-evident cornerstones of society. Like most Basques, he regarded work as something positive to contribute to a better society, regardless of one’s origin. Yet when he looked around him, he saw that wages and wealth were unevenly distributed and that not everyone had access to the same education opportunities. He sought a way to tackle it and his efforts eventually led to the creation of the Mondragon Group, a collection of commercial cooperatives with three basic values: fair work, decent pay and access to education.”

Employees Are Members, Members Are Employees

Today the Mondragon Group consists of 101 cooperatives, all of which are fully owned by their members. The central organization, which has a coordinating role, is also structured as a cooperative. Of the group’s 75,000 employees, about 85 percent are a member of their cooperative. The remaining employees have temporary contracts. Ander explains: “Once you are a member of a cooperative, you have job security. For this reason, there is a selection process. Everyone starts with a temporary contract and if both parties agree, the employee can become a member after one to three years.”

Being a member means that you co-own the cooperative. What does that mean in practice, what are the benefits, and how does it create fair work and decent pay? Ander asserts: “It benefits you in every aspect. From internal decision-making to wage and profit distribution, and from job security to additional employment benefits.”

Members Co-decide

Ander continues: “Members together form the highest decision-making body within the cooperative. Every member has a vote in the general meeting and the most important decisions are taken there. Examples are the appointment of management, remuneration policy, profit sharing and other strategic business decisions. As co-decision makers, members are directly involved in the business, which increases their motivation and loyalty. What’s more, they also take an interest in the long-term well-being of the cooperative, which of course affects them and their families personally. In that sense direct democracy in the workplace leads to a long-term vision for the cooperative and society at large.”

Membership does not come for free, but requires a capital commitment. Ander: “When you become a member, a capital contribution is required. The cooperatives activities are partly funded with member contributions. The amount varies somewhat per cooperative, but it is on average around €15,000. There are loans available to finance this amount when necessary.” Employees are thus truly invested in their cooperative.

More Pay Through Even Distribution

When it comes to wages, the members ensure that they are fairly allocated. Ander explains: “The wage structure ensures a fair distribution among employees. The gross minimum wage in Spain is around €10,000 euros a year. The lowest paid employee in a Mondragon cooperative receives about one and a half times this amount, about €15,000 euros. As the highest paid employee, a CEO earns up to six times as much. This makes the reward system very attractive for people at the low-end of the wage pyramid.” We can imagine that it motivates employees to know that their work efforts translate into payment of their own salaries and not exuberant salaries and bonuses of their bosses.

Ander continues with some pride: “You will see the same equal distribution when it comes to profit. It is primarily beneficial to those who have done the work. Temporary employees get cash pay-outs, while members increase their invested capital, which they receive as payment when they leave or retire. Other parts of the profit are re-invested in the cooperative and in research and development.”

According to Ander, the additional employment benefits are also excellent. “One of the cooperatives arranges for sickness and retirement payments for the whole group. Our own schools and training programs allow employees to develop themselves further. And once you’re a member of a cooperative, you’re guaranteed a job for life. If your company is in trouble, the group will endeavour to place members with other cooperatives.”

What About the Challenges?

Sounds beautiful, really, but we wonder if everything goes that smoothly. We recall Fagor’s recent bankruptcy, until 2013 one of the largest cooperatives within the Mondragon group. Ander: “Unfortunately, after a number of difficult years, the curtain fell for the division that made household appliances. Around 1,800 members were affected and lost their capital. It shows that as a co-owner, you also carry business risk. Fortunately, the vast majority of employees found employment with other cooperatives. Three years later, only around 90 former Fagor employees are still without a job. Yet they receive unemployment benefits, thanks to the internal insurance.” We’re impressed; that’s what we call solidarity!

A Vision for Long-Term Success

Instead of short-term profit maximization, Mondragon is focused on creating sustainable employment opportunities. Ander: “Mondragon wants to contribute to a better society by providing people with decent work. Now, but also in 5, 50 and 100 years. In addition, we annually donate 10 percent of our profits to charities and associations in the community.” Ander is convinced that the Mondragon model contributes to the Basque success. “The region where most of our cooperatives are located has the lowest unemployment rate in Spain, invests the most in R&D and its wealth is the most equally distributed.” Surely that’s no coincidence.

Mondragon Attracts Young Talent

We drive back to Bilbao with Nico. We found him on BlaBlaCar, a carpooling website. The recently graduated engineer works at one of the Mondragon cooperatives. Not yet a member, he still praises the terms of employment and the working atmosphere. He considers himself lucky, as many of his fellow students in Gijón (in neighbouring Asturia) have difficulty finding a well-paid job. Mondragon’s business model and favourable working conditions make it an attractive employer, which attracts young talent, also from outside the region. And thanks to Mondragon hiring Nico, we can catch a ride in the car he bought from his first salary!

A Socially Sustainable Solution

We are impressed with the way Mondragon embodies honest work, decent pay and job security. The democratic structure, relatively small income differences and internal solidarity make Mondragon a good example of socially sustainable entrepreneurship. The group’s fitting motto sums ups what it stands for: “Humanity at work”.

The group also proves that a cooperative company can be successful in various sectors and can handle international competition. Finally, Mondragon’s remuneration and profit distribution schemes show that sharing wealth more equitably does not need to depend on fiscal policies, but can be implemented at the source. A major obstacle for a society in which wealth is more evenly distributed, i.e. political consensus, is thus taken away.

How Equality Drives Sustainability

With its policies on salary and profit distribution Mondragon sets an example for a more sustainable society. The social crises of increasing wealth inequality and growing unemployment is not limited to Spain, but is a global phenomenon. Evidence suggests that societies that are more equal – such as the Scandinavian countries – are happier as a whole. One could thus say that more equality drives social sustainability.

That is also good news for environmental sustainability. According to a UN study, there is a correlation between wealth inequality and environmental sustainability. Consumer behaviour is one of the most direct derivatives of wealth inequality. On both ends of the inequality scale, this has negative effects on sustainability. Consider the super-rich who consume excessively and live beyond the earth’s carrying capacity, while the poor spend their scarce money on cheap junk, which often are products and foods that are least environmentally and socially responsibly produced. Those consumer choices therefore negatively affect the entire supply chain and stimulate unsustainable production and working conditions.

Yet there is hope. The UN research also submits that the correlation between wealth inequality and environmental sustainability also works the other way around. The findings in this paper suggest that reduction of inequality will play an important role in achieving environmental sustainability. It is therefore no surprise that the UN has included the reduction of inequality in its Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s). Goal 10 aims to “reduce inequality within and among countries”. We would even contend that reducing inequality is a prerequisite to achieving environmental sustainability.

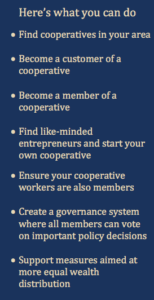

Cooperatives As Our Global Compass

There are various ways to create a more equal society. These are mostly debated in the political arena, like tax policies. Such policies are difficult to achieve, given that many politicians are against fiscal measures to redistribute wealth. Also, such measures are mainly aimed at correcting income inequalities that originate in the private sector. Wouldn’t it make much more sense to tackle income inequality at the source? This is exactly what cooperatives like Mondragon do. The model and success of the Mondragon group could therefore be a compass for the world. What a foresight that Basque priest had!

Related Sustainable Solutions

Circular Materials (NZL)

Waste does not exist in nature. Which circular materials can we use instead of plastic, so we can reduce human-produced waste?

Food Recue (NZL)

We meet organisations that lead the way in reducing food waste and learn that all of us have a responsibility to tackle this global challenge.

Fair Fashion (ALB)

In Albania, we meet Pitupi, which makes “people-to-people”clothing. Environmental and social values are as least as important as financial profit.

Local Currency (ITA)

We sail to Sardinia to visit the local currency Sardex. Could this be a more sustainable monetary alternative suitable to support a circular economy?

Mondragon Cooperatives (ESP)

At Mondragon, employees are owners, salaries and profits are fairly distributed, there is solidarity among cooperatives, and education is held in high esteem.