Rights for Nature (NZL)

In recognition of the Māori worldview, New Zealand granted rights to a forest, river, and mountain. Could this lead to better protection of nature and ultimately save humanity?

Contributes to achieving the following UN Sustainable Development Goals:

As we drive in our campervan through New Zealand’s countryside, we pass countless meadows with grazing sheep and cows. When we see trees, they are often part of immense plantations made up exclusively of non-native pine trees. It’s no surprise: the meat, dairy, and forestry industries are big business in New Zealand. Nature has to pay the price: biodiversity is low in these parts of the country. Where trees have been felled, a desolate landscape remains. “Once there was native forest here, teeming with life. What gives us the right treat nature like this?” Floris sighs. “It’s called progress”, Ivar responds, “at least according to the Western worldview.” Yet the consequences of centuries of looting nature can no longer be denied. Climate breakdown and the loss of biodiversity even threaten the survival of humanity. “You could even go as far as to say that the Western worldview is at the root of the challenges we are facing today”, Ivar sombrely adds. Would things improve if another worldview became more dominant, we wonder?

A Green Oasis

We soon get our answer. As we drive on, the monotonous pines abruptly make room for a huge variety of different trees, shrubs, and plants. We are engulfed by a sea of countless shades of green. “This is native forest”, Ivar rejoices. He slows down as the asphalt turns to gravel and the road becomes narrow and winding. “Let’s camp here and continue tomorrow”, Floris suggests. A dirt road leads to an open spot in the middle of the forest, where the birdsong is almost deafening. A stream with crystal clear water completes the picture-perfect setting. “This is what all of New Zealand must have looked like once”, Ivar muses.

We are in the middle of Te Urewera nature reserve, in the east of New Zealand’s North Island. The area is home to the Tūhoe, a Māori iwi (tribe). For centuries, they resisted British rule. Could that be the reason why nature is so pristine here?

Guardians of Nature

“We can’t own nature, we’re part of it”, Holly solemnly starts. We are at Te Urewera’s visitor centre, where Holly, a Tūhoe member, kindly answers our questions about the area. We don’t realise it at that very moment but with that sentence Holly turns our worldview completely upside down. She continues: “Nature is there when we are born, while we are alive, and after we die. We humans are just the kaitiaki, the guardians of nature. We must pass it on in a good condition to future generations.”

"We belong to the land, not the other way around."

Holly next explains why this nature reserve is special to her people. “In the Māori worldview, everything is connected. Not only the people, but also the mountains, rivers, animals, sea, and forests. They all originated from our ancestors: Ranginui, the god of the sky, and Papatuanuku, the goddess of the earth. Papatuanuku takes care of us, her children, through nature. So we belong to the land, not the other way around. Te Urewera is where we Tūhoe belong.”

Clash of Worldviews

The historical context explains why she emphasizes that last sentence. In 1840, the British signed a treaty with several Māori iwi, promising the Māori equality and sovereignty over their land. Instead, this Treaty of Waitangi accelerated the colonization of New Zealand, Aotearoa in Māori. Hundreds of thousands of British colonists arrived in the years that followed, with violent conquests as a result. Some Māori iwi were promised weapons and coins in exchange for their land. That was the crux of the matter: the British operated from the principle that people can own land. The owner has all the rights and can do whatever he wants with it. For the Māori, that concept did not exist. In their view, the land does not belong to anyone. Instead, the people belong to the land. People can reap the fruits of the land, but they must take good care of it. The local iwi decides who gets access to nature and who is allowed to cut trees, for example. A clash between the British and Māori worldviews was inevitable, with the British (or Western) worldview, aided by firepower and the sheer number of representatives, quickly dominating New Zealand society and laws.

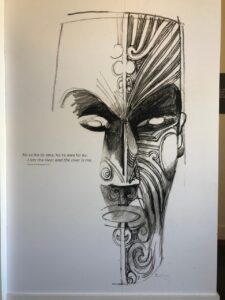

"Te Urewera is a place with its own identity and mana."

Legal Personality for Te Urewera

The Tūhoe never signed the Treaty of Waitangi and resisted relinquishing the lands of which they were the guardians. When it was suspected that the Tūhoe harboured a prominent Māori resistance fighter in Te Urewera, the British troops invaded the area, burnt the homes and crops of the Tūhoe and confiscated their land piece by piece. Years later, the land was designated as a national park. One might think that such designation would give sufficient protection to nature but Holly disagrees. “We wanted recognition of the spiritual value that Te Urewera has for us Tūhoe. To us, it is a place with its own identity and mana (soul or energy). It is our homeland and the basis for our culture, our customs, our entire existence. When it was a national park, we felt like guests here.”

That only changed in 2014, a special law was passed which confirmed that Te Urewera has its own legal personality and could never be appropriated or sold. The Tūhoe were recognized as guardians. “That’s when we felt at home again. Now we can take good care of Te Urewera”, Holly smiles.

This law also protects the natural state and biodiversity of the area. A board of trustees made up of Tūhoe and government representatives can represent Te Urewera. “So that means that lawsuits can be filed on behalf of the nature reserve?” Floris asks. “In theory yes”, Holly replies. “But that hasn’t been necessary yet, and that’s not the way we prefer to resolve conflicts.”

Assimilation of Worldviews

According to Holly, legal recognition sends a clear signal. It is now codified in law that people cannot do whatever they want in the area. Anyone who cuts trees without permission, for example, will be held accountable. “We try to convince everyone to respect our customs. That is not always easy, even within our own community. Some Tūhoe opt for financial gain at the expense of nature”, Holly sighs.

With that, Holly touches on an important topic. By giving Te Urewera legal personality, an attempt was made to integrate the Māori worldview into the Western legal system. The law provides an important new instrument for protecting nature: the legal process. But in practice, it is perhaps even more important that the Māori worldview was given such a prominent status, which could lead to more people applying it in their dealings with nature.

At the same time, the importance of legal recognition should not be underestimated. It was unique that a piece of nature received the same legal protection as people and companies. Before 2014, this was not laid down in law anywhere in the world. The recognition in law validates a different perspective: one wherein nature is at least equal to man and man’s creations.

River and Mountain with Rights

Te Urewera had the world premiere in 2014. Since then, two more natural phenomena in New Zealand have become legal entities: the Whanganui River and Taranaki Maunga (Mount Taranaki). We decide to take a look there, too.

The Whanganui River is shrouded in Māori tradition. According to legend, the river started as a teardrop from sky god Ranginui, while its path was created when Ranginui’s son Taranaki made his way from the North Islands central mountains to the coast. The local tribes regard the river as a sacred being of which they are part. “I am the river and the river is me”, is a proverb of the Whanganui iwi. They rely on the river for spiritual, cultural and physical sustenance. Yet the river and its surroundings are threatened by pollution, commercial forestry, industrial agriculture, and construction.

Taranaki Maunga is only an hour’s drive from the river mouth. The volcano is a perfect cone and stands tall in the middle of the flatland. The local iwi revere the mountain for its high spiritual value. The hike to the summit, 2,500 meters above sea level, is one of the most challenging we ever did. To respect the sacred peak, we take in the stunning view from a small platform close to it. We learn that introduced goats, weasels, stoats, possums, and rats all cause a decline in native plants and birds, thereby destroying the ecological vitality of the mountain.

At the Whanganui River and Taranaki Maunga, the local iwi are taking measures to restore nature and prevent further degradation. The legal recognition of the river and mountain allows them to better fulfil their important role as guardians. In both cases, like at Te Urewera, a trustee board made up of iwi and government representatives has been set up with the task of looking after the river’s and mountain’s interests. It means that there are now distinct bodies with clear mandates to protect and restore natural ecosystems. The local iwi finally have the tools and authority to fulfil their roles as kaitiaki. What’s perhaps even more important, is that the Māori worldview in which all things in nature are connected and need our respect and guardianship has been confirmed a second and third time in New Zealand.

Learning from the Māori

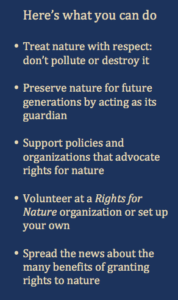

Giving rights to nature has more than symbolic value. That is the most important lesson we can learn from these examples. It validates a radically different relationship between man and nature. That worldview holds that we treat nature with the utmost respect, do not pollute or destroy it, and do not take more than it can give us. Only by living up to those principles, we can ensure that areas of special significance are preserved for future generations.

Once we recognize, like the Māori, that man is part of nature and depends on it, we need to take the next step, which is to fulfil our role as kaitiaki, guardians, of nature. It’s a worldview that provokes a different way of thinking. Yet it is precisely those insights that are necessary to protect nature all around the world and thus, ultimately, to save ourselves. We are convinced that giving rights to nature, as the New Zealanders have done, helps to elevate a worldview in which nature is worth protecting. The more countries and people adopt that worldview, the better our chances of passing nature on to future generations become.

Related Sustainable Solutions

Ubuntu – We Are Because the Earth Is (ZAF)

In South Africa, we explore Ubuntu, which puts humanity and cooperation above selfishness. Could it address today’s social and ecological challenges?

Connected to Country (AUS)

The Aboriginals, the first Australians, survived on their continent for more than 60,000 years. What can we learn from them to live more sustainably?

Rights for Nature (NZL)

In recognition of Māori worldview, New Zealand granted rights to a forest, river, and mountain. Could this lead to better protection of nature and ultimately save humanity?

Ancestral Values (CHL)

Easter Island’s famous statues not only attract tourists, but also symbolize ancestral values and even drive many sustainable initiatives.